Dr Ahsan Tariq , MBBS, MRCP (UK ) ongoing, IMT ( Internal Medicine Trainee, NHS England), GMC : 7805049

Dr Ahsan Tariq is a UK-registered medical doctor with a background in internal medicine and a focus on evidence-based research in cognitive health and nootropics. He critically reviews scientific studies, supplements, and ingredients to help readers make informed, safe, and effective choices for brain health and performance.

Introduction

Insulin sensitivity is one of the most critical yet misunderstood aspects of human metabolism. In modern health discussions, the term “Insulin Sensitivity Factor” is increasingly used to explain how efficiently the body responds to insulin and maintains blood glucose balance. While improving insulin sensitivity is often promoted as a universal health goal, it is not without complex biological limits and potential risks when misunderstood or misapplied.

This comprehensive theoretical guide explains the Insulin Sensitivity Factor from first principles, explores its physiological importance, evaluates its proven benefits, uncovers hidden risks, and presents evidence-based understanding supported by scientific research.

Understanding Insulin Sensitivity Factor

What Is Insulin?

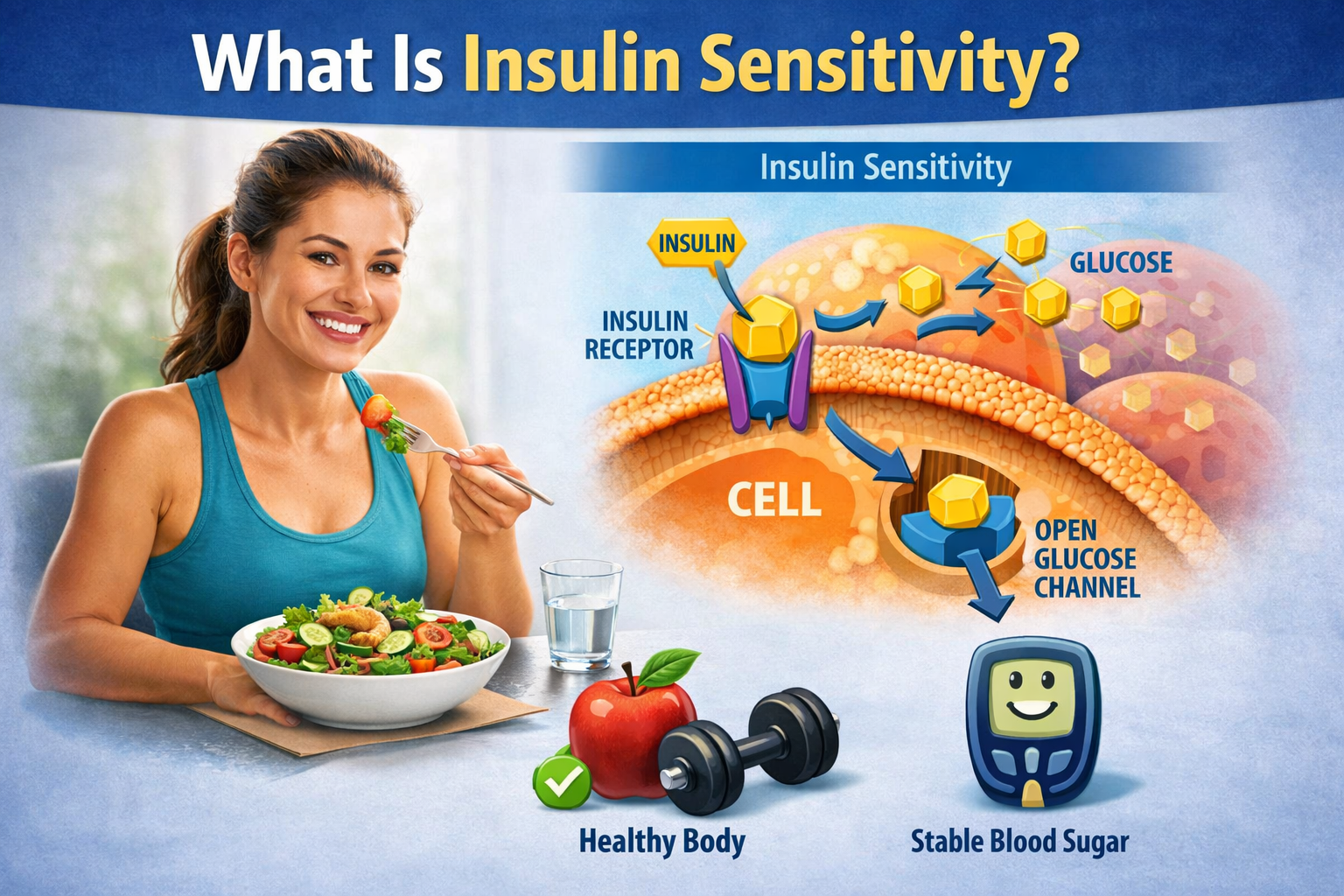

Insulin is a peptide hormone secreted by the beta cells of the pancreas. Its primary function is to regulate blood glucose levels by facilitating the uptake of glucose into muscle, fat, and liver cells. According to early metabolic research, insulin acts as a “key” that unlocks cells so glucose can enter and be used for energy or stored for future needs [1].

Beyond glucose control, insulin also influences:

- Fat storage and lipolysis

- Protein synthesis

- Electrolyte balance

- Cellular growth signaling

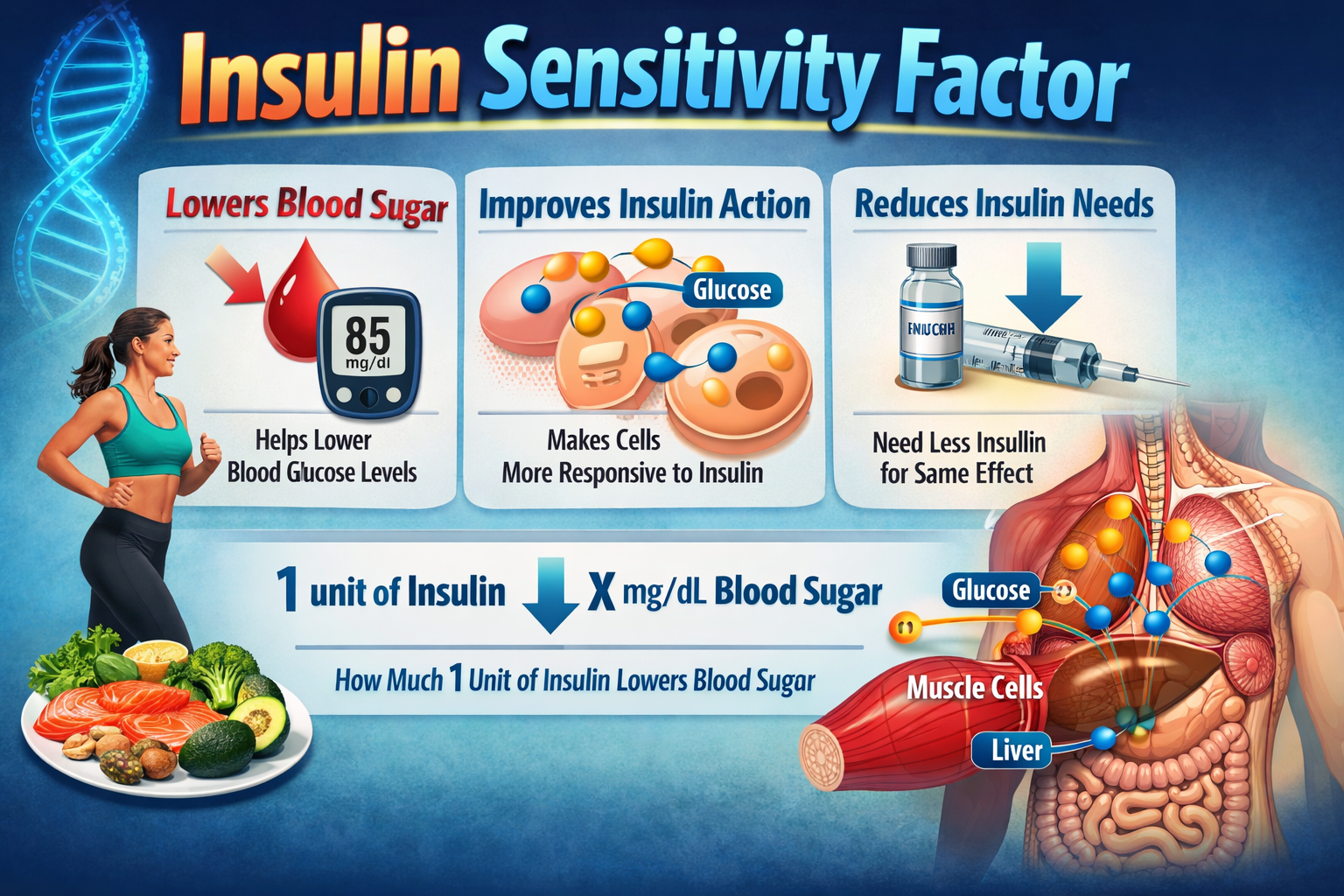

Defining Insulin Sensitivity

Insulin sensitivity refers to how responsive the body’s cells are to insulin. When insulin sensitivity is high, a small amount of insulin is sufficient to lower blood glucose. When sensitivity is low, the body requires more insulin to achieve the same effect, a condition known as insulin resistance [2].

The Insulin Sensitivity Factor (ISF) is a conceptual and clinical measurement that estimates the glucose-lowering effect of insulin within the body. It is widely used in metabolic research and clinical diabetes management to evaluate insulin efficiency [3].

Theoretical Meaning of Insulin Sensitivity Factor

From a theoretical standpoint, the Insulin Sensitivity Factor reflects:

- Cellular receptor efficiency

- Intracellular glucose transport mechanisms

- Hormonal balance

- Mitochondrial energy utilization

A higher ISF indicates better metabolic flexibility, while a lower ISF signals impaired metabolic regulation [4].

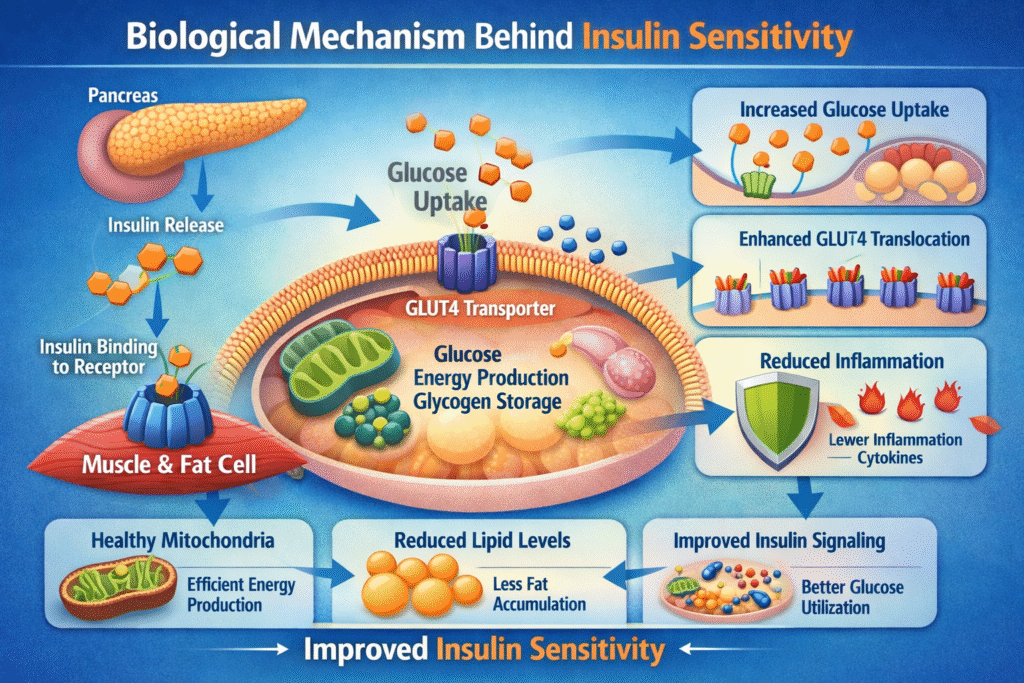

Biological Mechanism Behind Insulin Sensitivity

Insulin Receptor Function

Insulin binds to specific receptors on cell membranes. This binding activates a cascade of intracellular signaling pathways that allow glucose transporters (primarily GLUT4) to move glucose into cells [5].

Impairment at any step of this pathway reduces insulin sensitivity.

Role of Muscle, Liver, and Fat Tissue

Different tissues respond to insulin in distinct ways:

| Tissue Type | Role In Glucose Metabolism | Impact On Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle | Primary glucose disposal | Strong influence |

| Liver | Regulates glucose release | Moderate influence |

| Adipose tissue | Stores excess energy | Regulatory influence |

Skeletal muscle accounts for nearly 80% of insulin-mediated glucose uptake, making muscle health central to insulin sensitivity [6].

Importance of Insulin Sensitivity Factor in Overall Health

Metabolic Stability

High insulin sensitivity promotes stable blood sugar levels, preventing excessive fluctuations that stress the endocrine system. Long-term stability reduces metabolic wear and tear [7].

Hormonal Balance

Insulin interacts with other hormones such as cortisol, growth hormone, estrogen, and testosterone. Imbalances in insulin sensitivity can disrupt this hormonal network [8].

Proven Benefits of High Insulin Sensitivity

Improved Glucose Regulation

High insulin sensitivity allows efficient glucose clearance from the bloodstream. According to longitudinal studies, individuals with greater insulin sensitivity have a significantly lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes [9].

Reduced Risk of Metabolic Disorders

Improved insulin sensitivity is associated with:

- Lower triglycerides

- Reduced LDL cholesterol

- Improved HDL cholesterol levels

These changes collectively reduce cardiovascular disease risk [10].

Weight Regulation and Fat Metabolism

Insulin is a storage hormone. When sensitivity is high, insulin is released in appropriate amounts, preventing excessive fat storage. Research confirms insulin-sensitive individuals lose fat more efficiently under calorie-controlled conditions [11].

Enhanced Physical Performance

Insulin sensitivity improves nutrient delivery to muscles, supporting:

- Faster recovery

- Improved endurance

- Increased muscle protein synthesis

Athletic studies highlight insulin sensitivity as a performance-enhancing metabolic trait [12].

Reduced Chronic Inflammation

Insulin resistance is closely linked with chronic low-grade inflammation. Improved sensitivity lowers inflammatory biomarkers such as TNF-α and CRP [13].

Hidden Risks Associated With Insulin Sensitivity Mismanagement

Hypoglycemia Risk

Excessive insulin sensitivity, particularly when combined with glucose-lowering medication or extreme dietary restriction, can cause dangerously low blood sugar levels [14].

Nutritional Deficiencies

Overemphasis on insulin control may result in:

- Inadequate carbohydrate intake

- Fiber imbalance

- Micronutrient deficiencies

Extreme dietary patterns can negatively affect long-term health [15].

Hormonal Disruption

Overtraining, severe caloric restriction, or chronic stress can paradoxically impair insulin sensitivity by elevating cortisol levels [16].

Misuse of Supplements

Many supplements claim to “optimize insulin sensitivity,” yet evidence remains inconsistent. Unregulated use may interfere with glucose metabolism [17].

Factors Influencing Insulin Sensitivity Factor

Dietary Patterns

High-fiber diets improve insulin sensitivity by slowing glucose absorption and improving gut microbiota diversity [18].

Physical Activity Levels

Exercise increases insulin sensitivity independently of weight loss. Both aerobic and resistance training enhance GLUT4 activity [19].

Sleep Quality

Sleep deprivation reduces insulin sensitivity by up to 30%, according to controlled sleep studies [20].

Psychological Stress

Chronic stress activates hormonal pathways that reduce insulin receptor efficiency [21].

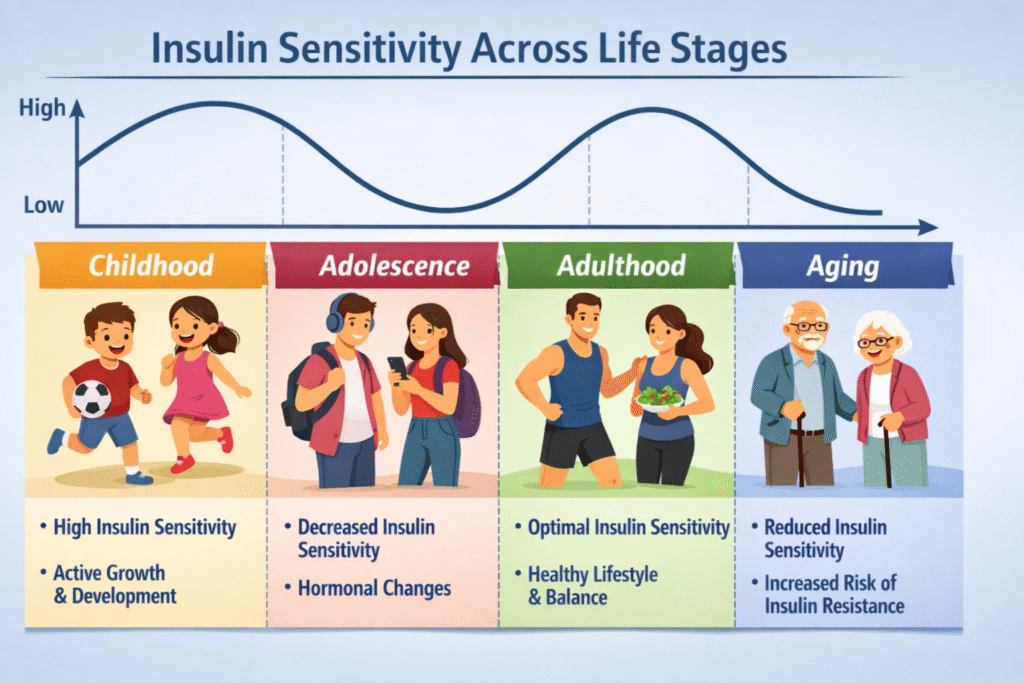

Insulin Sensitivity Across Life Stages

Childhood and Adolescence

Temporary insulin resistance can occur during puberty due to hormonal changes, usually resolving in adulthood [22].

Aging Population

Insulin sensitivity declines with age due to muscle loss, mitochondrial dysfunction, and reduced physical activity [23].

Gender Differences

Sex hormones influence insulin sensitivity, with estrogen offering protective effects before menopause [24].

Common Myths About Insulin Sensitivity

“Only Diabetics Should Care”

Insulin sensitivity affects energy levels, weight control, and disease prevention in all individuals [25].

“Zero Carbs Equals Perfect Sensitivity”

Balanced carbohydrate quality matters more than elimination [26].

“Supplements Are Enough”

Lifestyle changes remain the foundation of insulin sensitivity improvement [27].

Public Health and Economic Impact

Insulin resistance contributes significantly to global healthcare costs due to its link with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity [28].

Future Directions in Insulin Sensitivity Research

Emerging research focuses on:

- Personalized nutrition

- Continuous glucose monitoring

- Genetic and microbiome-based interventions

These approaches may refine insulin sensitivity optimization in the future [29][30].

Conclusion

The Insulin Sensitivity Factor is a cornerstone of metabolic health. Its benefits include improved glucose control, enhanced metabolism, and reduced disease risk. However, misunderstanding its limits or pursuing extreme strategies may introduce hidden risks.

A balanced, theory-driven, evidence-based approach remains the safest and most effective way to support insulin sensitivity across the lifespan.

References

- Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Nature, 2001.

- DeFronzo RA. Diabetes Care, 2004.

- Wilcox G. Clin Biochem Rev, 2005.

- Reaven GM. Diabetes, 1988.

- Czech MP. Cell, 2017.

- Petersen KF et al. Science, 2003.

- Tabák AG et al. Lancet, 2012.

- Rosmond R. Obes Res, 2005.

- Hu FB et al. JAMA, 2001.

- Grundy SM. Circulation, 2002.

- Hall KD et al. Am J Clin Nutr, 2015.

- Ivy JL. Sports Med, 2004.

- Shoelson SE et al. J Clin Invest, 2006.

- Cryer PE. Endocrinol Metab Clin, 2010.

- Ludwig DS et al. BMJ, 2018.

- Hackney AC. Horm Behav, 2006.

- Bailey CJ et al. Diabetes Care, 2004.

- Slavin JL. Nutrients, 2013.

- Hawley JA, Lessard SJ. J Physiol, 2008.

- Spiegel K et al. Lancet, 1999.

- McEwen BS. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2007.

- Moran A et al. Diabetes Care, 1999.

- Chang AM, Halter JB. Endocr Rev, 2003.

- Tramunt B et al. Endocr Rev, 2020.

- Reaven GM. Am J Clin Nutr, 2005.

- Jenkins DJ et al. Am J Clin Nutr, 2002.

- Suksomboon N et al. Diabet Med, 2011.

- International Diabetes Federation, 2023.

- Zeevi D et al. Cell, 2015.

- WHO Metabolic Health Report, 2022.

One thought on “Insulin Sensitivity Factor: Proven Benefits And Hidden Risks”